- Home

- Mia Freedman

Mama Mia Page 2

Mama Mia Read online

Page 2

Reluctantly, I stashed my sad little portfolio in the back of a cupboard and retired. Being briefly mistaken for a model by Cleo’s fashion editor was the pinnacle of my non-existent modelling career.

Just to be sure she was talking to me, I looked over my shoulder. The other grey plastic chairs were empty. Excellent. ‘Oh, no, I’m just, um, waiting to see Lisa Wilkinson,’ I stammered, failing to hide the brag in my voice. You see, my goals had changed. I no longer wanted to be a model. I wanted to be a journalist. More specifically, I wanted to work on a magazine. Even more specifically, that magazine had to be Cleo. It just HAD to be.

CLEO NERD

Answering machine message to my mum from me:

‘Oh my God, Mum, guess what? Lisa Wilkinson wants to see me! I have an interview with her next week. I’m so excited! Can I borrow the car?’

The only thing better than waiting to see Cleo’s fashion editor was waiting to see Cleo’s editor. But if the fashion editor was deeply impressed that I had an interview with Lisa, she hid it well. With a polite smile and a flick of her long blonde ponytail, she vanished back into the office.

Her name was Diana and I knew this with certainty because I’d spent years studying the staff list that appears in the front of every magazine. I’d eagerly matched those names with the captions on staff snapshots which sometimes appeared on the editor’s page. I was a Cleo nerd.

For years, I’d idolised the women who worked on the magazines I loved. How could it be possible to have a better job, I wondered, even though the concept of having a job was still a very vague one. Like having a baby.

As a teenager, my favourite part of Dolly had always been the editor’s letter and I pored over every detail about what was happening in the office and what the staff were doing.

As with any magazine, the queen of Dolly was its editor; back then it was Lisa, although she never came across as a queen. With waist-length straight brown hair, a radiant, open face and a friendly smile, she seemed just like a grown-up version of me or any other girl. Real. Approachable. That was Lisa’s skill and appeal, inside and out—and still is today.

It would be decades until the head shots on editors’ pages would become as glamorous, stylised and air-brushed as the fashion pages. In the 1980s, Lisa had the same small and unglamorous picture on her page every month. Occasionally she’d update it, maybe once a year. In her editor’s photo, she’d usually be sitting at her desk, not wearing much make-up, in no tricky outfit. Just her big smile and her long hair. Sometimes, glasses. Maybe a jumper. Her image was that of a regular Aussie girl. Who just happened to have a job beyond my wildest dreams.

I’d first begun to buy magazines as a schoolgirl, looking for photos and headlines to paste into my school diary and onto my folders. It was instant love.

My fascination with magazines was so extreme that my monthly Dolly fix soon wasn’t enough. Even though I was twelve, I began to buy magazines aimed at my mother (who never showed any interest in reading them) like Woman’s Day, the Australian Women’s Weekly and New Idea. With their breezy gossip and lifestyle content, they appealed to me over Cosmo and Cleo, which felt too raunchy and sophisticated. Sometimes I bought them anyway, but Dolly was my favourite—the mag with which I identified most passionately.

One hot summer day when I was about fourteen, I was slathered in baby oil, sunbaking in the garden with my brand-new copy of Dolly. With that familiar rush of excitement and anticipation, I turned automatically to the editor’s page. One paragraph in and I was traumatised. Lisa was leaving. It was her last issue as Dolly’s editor. She wrote about how much she’d miss the staff and the readers and how much she was looking forward to her new challenge: editing Cleo.

This was devastating news. I wasn’t ready to move to Cleo with her. I wasn’t ready to grow up and leave Dolly behind. I felt bereft and abandoned in that dramatic, self-absorbed way teenage girls have of placing themselves in the centre of any given event.

In time, I healed. I stayed loyal to Dolly for another year or two but I never bonded with the editors who followed Lisa. No one could take her place or strike the same self-deprecating yet aspirational tone of her editor’s letters.

Eventually, at about sixteen, I was ready to graduate to Cleo. I quickly found myself a new love. Cleo had the Aussie familiarity of Dolly but with an irreverent cheekiness and intelligent tone that appealed to women all the way into their thirties.

Dolly, Cleo and Cosmo were each aimed at a far older audience in the seventies, eighties and even nineties than they are today. Mostly because there were far fewer magazines to choose from. The typical progression for an Aussie girl was to buy Dolly when you were a teenager, then Cleo or Cosmo during your twenties and thirties, and, finally, when you got married and had kids, you bought the Women’s Weekly, where you stayed till you died. As the adage went, ‘Dolly teaches you what the word orgasm means, Cleo teaches you how to have an orgasm and the Women’s Weekly teaches you how to knit one.’

Being the teenage magazine junkie I was, I bought Cosmo as well, but for me it was always a poor relation. Cleo was my true love. My perfect magazine match.

In a stroke of luck, after leaving school I met a girl whose father worked for the Packer family, who owned Australian Consolidated Press. He wasn’t with the magazine division but he worked in the same building. I jumped at the chance to write this poor man a very formal letter BEGGING for the chance to work in magazines and mentioning my particular devotion to Cleo and to Lisa.

I hand-delivered my letter to his secretary, taking the bus into the city and walking awestruck into the building that housed all my favourite magazines. At the time, ACP published Dolly, Cleo, Cosmo, the Australian Women’s Weekly, Harper’s Bazaar, Woman’s Day, House & Garden, Elle, Mode, Wheels and dozens of other titles.

Many people don’t realise—I didn’t—that even though many of these magazines compete with each other, they all share an owner and publisher. And building. The same one I’d soon be walking into every day for the next fifteen years.

I will forever be grateful that my schoolgirlish letter and woefully inadequate CV was passed on to Lisa. When you’re an editor, you receive dozens and dozens of similar unsolicited letters every week and, unfortunately, most go ignored. There’s just no time and no space to accommodate every girl who dreams of a magazine career.

I’ve always remembered the kindness that was shown to me and the invaluable chance I was given, at nineteen, to prove myself to Lisa. It was the elusive foot in the door.

In six years’ time, I’d be an editor myself and count Lisa among my close friends. We would have babies in the same week—her third, my first. Six years after that, I’d be responsible for Cleo, Cosmo, Dolly and several other magazines in the building. But at that moment, as a precocious, pimply teenager waiting on a grey plastic chair to meet her for the first time, I was absolutely terrified.

‘Sorry to keep you waiting; she’s ready to see you now.’ Susan, Lisa’s assistant, showed me into her office, and while walking the three metres from reception, I nearly tripped on some loose carpet being held down with masking tape. Nice.

Lisa greeted me with a smile and gestured for me to sit in one of the dilapidated chairs opposite her desk. Later, I would learn the history of this infamous chair. Once, when Kerry Packer walked into Lisa’s office for a meeting, he’d sat in it and promptly tipped over backwards onto the floor. Me, I just perched carefully and tried to process my surroundings. I kept getting stuck at the part where I was actually sitting in front of Lisa Wilkinson. In her office. While she sat behind her desk casting a polite eye over my unimpressive CV.

Highlights included part-time jobs as a checkout chick at Woolies and a sales assistant at fashion chain Cherry Lane during high school. I’d loved those jobs. My parents had instilled a strong work ethic in me early. My older brother had worked at David Jones when he was at high school, and more than anything I wanted to be like him. I applied to be a checkout chick as soon as I hi

t Woolworths’ minimum age requirement for casuals: fifteen. This was before scanning, mind you. When you had to find a price tag on every item and punch the number into the cash register. By hand. I did one or two shifts per week through much of Year Eleven and the money came in handy for going out on weekends.

After leaving school, I’d decided to defer university for a year and live in Italy for six months with three girlfriends. To fund my trip, I worked as a waitress in a posh restaurant serving salads to Ladies Who Lunched. It was unspeakably tedious. By the end of it, I hated people, food and utensils, but I’d saved my airfare and some spending money. My parents generously kicked in some extra.

The idea had been to study Italian in Florence but we spent much more time in bars, nightclubs and cafés than we did attending classes. I came back with conversational Italian and ten extra kilos.

I then spent the next nine months at university, studying Arts–Communications and majoring in journalism. I was living at home and working part time as a promotions girl at car shows as well as waitressing again to make some cash.

University was not going well. I was bored, frustrated and impatient. After the firm boundaries and strict school rules that had helped me do well in the HSC, I lacked the discipline for university. Uninspired by the process of learning, I was plagiarising my journalism assignments from a local gay newspaper, which was particularly brainless given that my lecturer was gay. I began to skip lectures and I was struggling to stay focused. (Thoughtfully, I’d left those last few points off my CV.)

After skimming what was in front of her, Lisa glanced up at me, smiled wryly and said, ‘So, Mia. You went to a private girls school. You just spent six months in Florence and you live in the eastern suburbs. Why shouldn’t I hate you?’

Her tone was not unkind but there was an unspoken challenge in what she said: are you a precious princess? This was classic Lisa. In an instant, she’d extracted the pertinent details from my patchy CV and made a valid point veiled with humour.

I can’t remember how I replied, probably by saying something inspired like ‘Cleo is my favourite magazine!’, but I do recall her launching into the ‘Magazines are not glamorous’ speech. This was one I would come to recite dozens of times myself to hopeful, naïve girls sitting on the other side of my own (future) desk.

After listening patiently to me babble about how much I loved writing and how my favourite subject at school was English and blah blah blah, Lisa suggested I come and do work experience for a fortnight, assisting the features editor. I couldn’t say yes fast enough, although a small, arrogant voice in my head grumbled with disappointment at not having been offered a full-time, paying job on the spot. Because that’s what I wanted.

As Lisa walked me to the door of her office, she said something I’d never forget. ‘You know, Mia, magazines aren’t for everyone. You might be better suited to a different form of journalism like newspapers or TV. Or radio. Magazines are either in your blood or they’re not.’

She was absolutely right about that. For the next fifteen years, I would live for magazines. In my blood? You bet.

WOULD YOU LIKE 8000 FREE LIPSTICKS WITH THAT?

Answering machine message to Lisa’s PA from me:

‘Um, hi Susan, it’s Mia calling again. I know we spoke yesterday but just wondering if Lisa had made a decision about the beauty editor position yet because, you know, well, I’m pretty keen to find out. Sorry to hassle. Gosh, I don’t mean to be a stalker or anything and I know you’re probably flat out and—“beeeeeeeep”’

It’s no accident that so many editors begin their magazine careers as beauty editors. Cleo, Vogue, the Australian Women’s Weekly, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, Shop Til You Drop, Dolly, Girlfriend, InStyle, Yen, House & Garden, Cosmo and Madison have all had editors who started that way.

To be a proficient beauty editor, you need three key skills, all of them—plus more—required by good editors. First, you need to be an outstanding ambassador for your magazine. A personification of the brand. This is because you spend a large chunk of your time outside the office at functions, representing the magazine to advertisers and the media. You’re the staff member most likely to appear in the social pages because the editor and everyone else are back at the office, writing, designing, shooting, sub-editing. Meanwhile, you are on the frontline. It’s like Afghanistan…with mascara and gift bags. So it’s vital to look the part.

You must be well groomed and well behaved. You must know how to make small talk and subtly sell your magazine to advertisers who are persistently trying to flog their products to your readers via you. Bedhead and a hangover won’t cut it. Neither will shyness. Or too much free champagne.

The endless daily churn of product launches and lunches may seem superficial because…oh wait, it is. But the champagne and canapés belie your true mission: to suck up to the advertisers.

This is the second way in which a beauty editor is a lot like an editor. In both jobs, you straddle the two different worlds of magazines, editorial (the pages created by the magazine’s staff) and advertising (paid pages created by advertisers). A smart beauty editor can lubricate the passage of advertising dollars from the client into the magazine. She understands both the implicit and explicit connections between advertising and editorial. She knows how to keep clients happy without compromising her editorial integrity. Well, no more than she has to, anyway.

It’s an open secret that big advertisers are looked after on the editorial pages of virtually every magazine in which their ads appear. There is so much competition for a limited pool of advertising dollars that ethical lines are often blurred. The basic equation is simple: we’ll give you positive editorial mentions for as long as you give us advertising dollars.

The specifics of this relationship depend upon the type of magazine and its circulation. On some titles, ‘looking after’ may mean a guaranteed number of editorial mentions or just a mutual understanding that the client’s products will be featured positively and frequently on the editorial pages. But it’s not quite as simple as cash-for-comment. Not always. If an advertiser pays tens of thousands of dollars to buy a dozen ad pages in your magazine, it will only be because their products are targeted directly to your readers’ demographic. Chanel won’t buy pages in Dolly, they’ll advertise in Vogue. So it’s not exactly a stretch for Vogue to write about Chanel lipstick. That’s where the skill of the beauty editor comes into play. If you know you have to suck up to a particular advertiser, it’s your job to find a way to do it without openly lying to your readers. First you find a product you genuinely like and then you find a genuine reason to write about it.

Sometimes, though, it’s plainly dodgy. Smaller, lower circulating titles have to bend over much further to secure ad dollars, often publishing entire suck-up stories about the launch of, say, a new perfume or eye cream under the guise of editorial. Fashion magazines are particularly prone to running these kinds of ‘stories’.

These are not to be confused with ‘advertorials’, which are paid advertising pages created to look like editorial. Advertorials are often conceived, written and designed by the editorial staff, who do this on their own time for freelance rates. The idea of an advertorial is to integrate the advertiser’s product into the editorial look and tone of the magazine. This is also known as trying-to-trick-the-reader.

Clients love advertorials because they blur the line between advertising and editorial. Editors hate advertorials because they blur the line between advertising and editorial—even though they have to run with a line at the top of the page saying ‘promotion’ or something similar. Editors think advertorials look ugly and compromise the quality of the surrounding editorial. Editors do not like to trick the reader because readers do not like to be tricked. It makes readers angry and cynical, and it erodes their loyalty. But the more advertising pages your sales team can book, the more editorial pages you can run. So you shut up and you say thank you to your advertisers for their lovely advertorials.

; Until I worked in magazines, like many readers, I had a common complaint. ‘Why are there so many damn ads?’ I’d whinge, flicking crankily past glossy advertisements for lip gloss and sports bras. The answer is a purely economic one: the advertising pages pay for the editorial ones. All magazines work on a strict advertising to editorial page ratio. This ratio depends on the business model of the magazine, but at Cosmo a typical issue was about sixty per cent editorial, forty per cent advertising.

Most magazines sold on news-stands (as opposed to the ones that come free in a newspaper) have two revenue streams. The first comes from the cover price and the second is from advertising pages. But not all work that way. Some magazines are purely circulation models, like Take 5 and That’s Life which sell hundreds of thousands of copies but don’t carry much advertising. Others are advertising models—typically, prestige magazines that sell, say, fifty thousand copies but whose wealthy readers are very attractive to advertisers. That’s why magazines like Belle, Gourmet Traveller and Vogue have so many advertising pages.

The publishing industry uses ad count as one way to measure the health of a magazine. Generally, a mag full of ad pages is more likely to be profitable and successful than one with only a few.

Beauty editors know all of this. The clever ones do, anyway. They have to because the bulk of advertising in a glossy mag like Cleo or Cosmo comes from beauty companies. As the only person apart from the editor who has regular contact with the advertiser, they develop an intrinsic understanding of the delicate balance between editorial integrity and the crucial revenue that ad dollars provide.

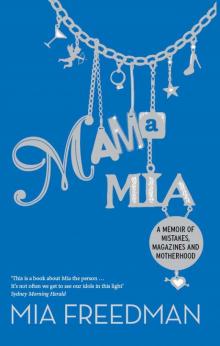

Mama Mia

Mama Mia